1

/

of

1

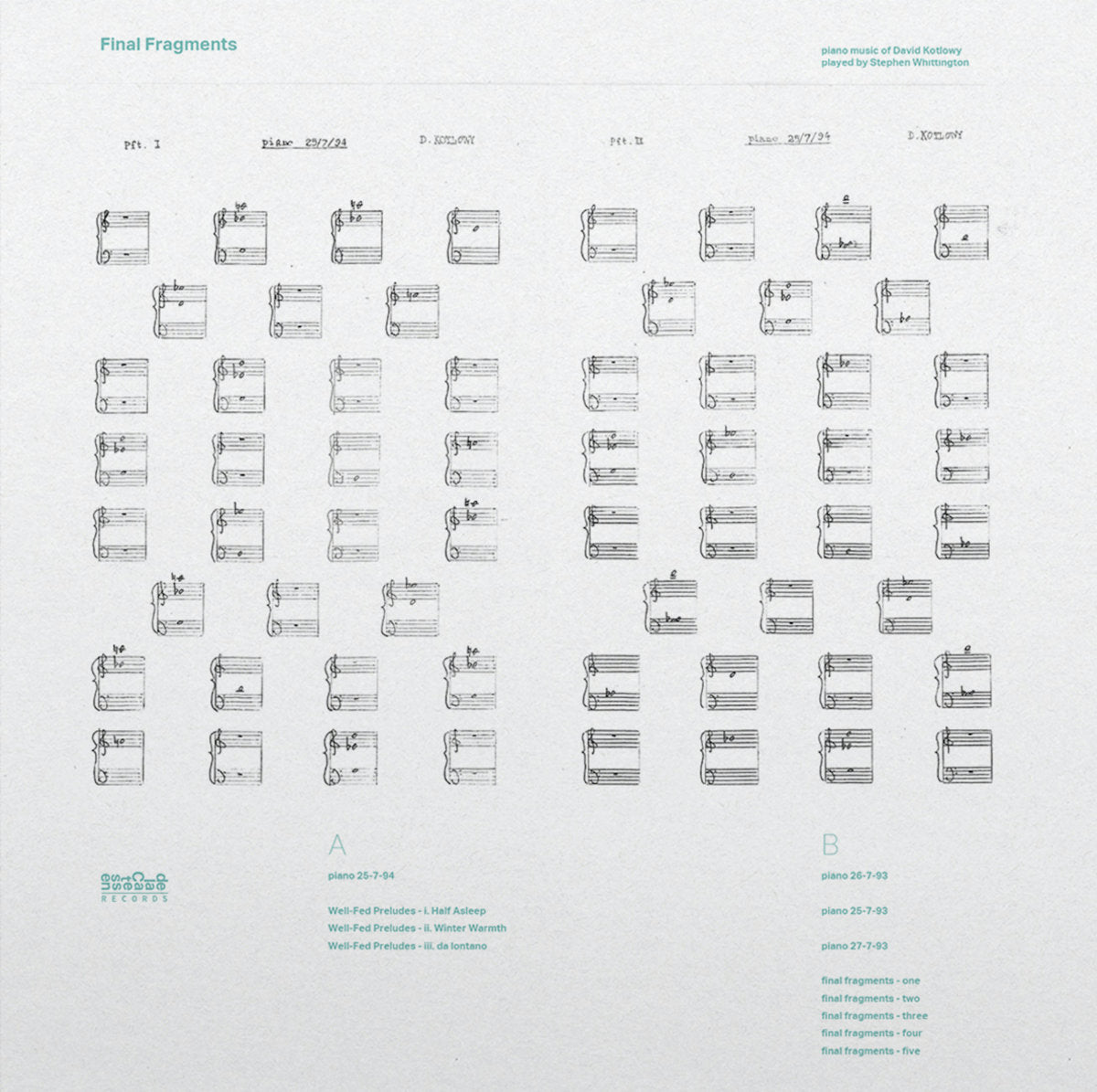

Stephen Whittington - Final Fragments - piano music of David Kotlowy LP

Stephen Whittington - Final Fragments - piano music of David Kotlowy LP

Regular price

$39.95 AUD

Regular price

Sale price

$39.95 AUD

Unit price

/

per

Taxes included.

Shipping calculated at checkout.

By the time I landed in Adelaide somewhere in the mid 1990s, to complete my secondary schooling and get the hell out of Dodge – the tiny country hamlet that I’d been living in, in the northern parts of the Upper Hunter in New South Wales, at the foot of the Barrington Tops – I’d already been indoctrinated into a set of ideals through my reading, listening, and the questionable guidance of a few family members. Foremost was a kind of ideological thoroughness borne of punk’s idealism, coupled with a notion that volume and noise were the radical edge of experimentalism (learned mostly through listening to the guitar groups of then-recent times – Sonic Youth, My Bloody Valentine, Loop, Spacemen 3, Band Of Susans, etc.)

Adelaide was both contextually vast – a ‘real’ city, the first one I’d lived in since Sydney in the ‘80s – and yet somehow limited, closed-off. I credit the latter to matters both personal (a propensity towards shyness) and cultural (a strange parochialism within the ‘indie rock’ circles I’d fallen into). The idea of silence and minimalism as virtues took a while to settle in. Discovering Morton Feldman via an article in a mid ‘90s issue of The Wire, I wondered what the hell I was reading about, and why I hadn’t known about it sooner. There seemed, to me, to be no parallel community or creative endeavour in the city I was living in. Truth was, I couldn’t have been more wrong if I’d tried.

I think the scales really fell from my eyes when I met Stephen Whittington, who was a guest lecturer in a popular music subject I took at the University of Adelaide, talking about the Velvet Underground and their connections with composers like La Monte Young. From there, it was a short step to seeing Whittington perform Feldman's Triadic Memories one evening on campus, one of the few times I can say, with conviction, that my listening to and understanding of music was irrevocably changed. (I ended up writing about this performance in The Wire.) I’d heard mention of the city’s history of experimental music practice, and of a few composers in that orbit – David Kotlowy’s name would be spoken not so much with reverence, though he was clearly highly respected, as with a questioning curiosity.

“I first met David sometime in the 1980s,” Whittington recalls, discussing his formative encounters with Kotlowy and his compositions, within the context of Adelaide’s cultural ferment. “Adelaide was basking in the afterglow of the 1970s – the Dunstan era – when it was the coolest city in Australia. There was still a lot of energy here. There were three competing music schools offering degrees in composition (there is only one now) and there were many composers in their twenties and thirties doing interesting things. It was quite a different scene from the Eastern states. In 1988 I organised the Breakthrough Festival of New Music; in addition to Adelaide composers, the program featured music by John Cage, Morton Feldman, Christian Wolff and La Monte Young. It was around this time that I first played David’s music.”

The history was all there, if you cared to look for it. There were two things I clearly needed to get over: my aesthetic blockages, and my residual Eastern states snobbery. “Adelaide’s musical identity was quite distinct in Australia,” Whittington continues, “and we had the feeling that provincial Adelaide was viewed by the rest of the country as a quaint curiosity stuck in a time warp. We were ignoring the radical developments in contemporary music, and therefore we could be safely ignored in turn. We, on the other hand, had the opposite feeling – we believed that we were the radicals. I still believe that. David was a vital part of the emerging identity of musical life in Adelaide that came into being in the 1980s and 90s; and he remains a vital part of it today.” With this LP, beautifully performed by Whittington, the wider world can hear Kotlowy’s quietly revolutionary compositions, up close, as quixotic and humbly moving as ever.

“The music in this LP comprises some of my early post-graduate work,” Kotlowy says, reflecting on the works compiled here. “Finding my own way through the spell of John Cage, Japanese aesthetics, and process music... My musical ethos was, and continues to be informed by Japanese musical aesthetics, particularly the desire to produce a maximum effect from a limited amount of material, and the principles of honkyoku shakuhachi.” From these constituent elements, guided by such principles, Kotlowy has navigated his way to a composer’s voice that admits limitation as inspiration, restriction as the spur to invention, and finds a way to reflect its forebears without ever being beholden to their voices.

Listening to these pieces, I can hear a gentle steeliness in their repose; these works are uninterested in excess, rather locating a sturdy eloquence in saying only what need be said. Adelaide composer, and De la Catessen label head, Luke Altmann recalls meeting Kotlowy at 2000’s Barossa International Music Festival, where the latter was a guest speaker in a student workshop. “At a time when many young composers were looking for ways to sound more impressive through filling in all the gaps in their scores, David’s gave counter-intuitive but sage advice: to look for things to leave out. Not to develop ideas, but to reduce them until only their essence remained, and that in itself would be your music.” Reflecting on the implications of this approach, Altmann concludes, “It seemed radically austere.”

It is also radically beautiful, and perhaps, most of all, radically human. This may come, at least in part, from Kotlowy’s interest in breath as a compositional tactic. The mid ‘90s pieces use breath to determine tempo and duration. “This is a direct influence of honkyoku shakuhachi music,” Kotlowy says, drawing parallels with the twelfth-century tradition that is associated with Zen Buddhism, “and is quite simple: relaxed inhalation at a bar line, then breathe out, playing the notes in the bar for the duration of the exhalation. Structurally, the breath phrasing acts like flexible time frames, and so, with musical duration intimately linked to a performer’s breath, the music achieves an elasticity and unpredictability that expresses the individuality of each musician and the singularity of each performance... The breath- based works are the heart (or perhaps the lungs) of my compositional output for the twenty years from 1990 to 2010.”

Elsewhere, there are the gorgeous Well-Fed Preludes, which Kotlowy reflects are “a clear acknowledgment of the music of Erik Satie, and America's West Coast minimalists,” and there’s a homage in the titling of 2003’s Final Fragments, drawing as it does from the titles of two Morton Feldman pieces, Last Pieces (1959) and Turfan Fragments (1980). “The sonic palette is larger than the earlier pieces,” Kotlowy acknowledges, “but the music is still restrained. I was aiming for a ‘beauty without biography’, a phrase Feldman used to describe his music.” Throughout, I am struck by the music’s poetics, its capacity to still the moment, and its ability to balance rigour of praxis with gentleness of touch. This surely is also down to Whittington’s masterful, beguiling performances.

Indeed, perhaps it’s best to leave the final word to Whittington, who summarises Kotlowy’s music with an acuity that I can only dream of. “His music is a prime example of Adelaide’s quiet (in several senses) radicalism. Time is measured organically, often by the human breath; there is a sense of space – it is as much about space as it is about sounds. The sounds are mostly soft, but not fragile. There is a calm certainty about their placement. The music invites you to listen, but it does not compel you. It draws you in, if you are open to it. All of this places particular demands on the performer, requiring a certain state of mind akin to meditation. A lot of music leaves you feeling drained at the end of it; David’s leaves you feeling energised.”

© Jon Dale, 2021