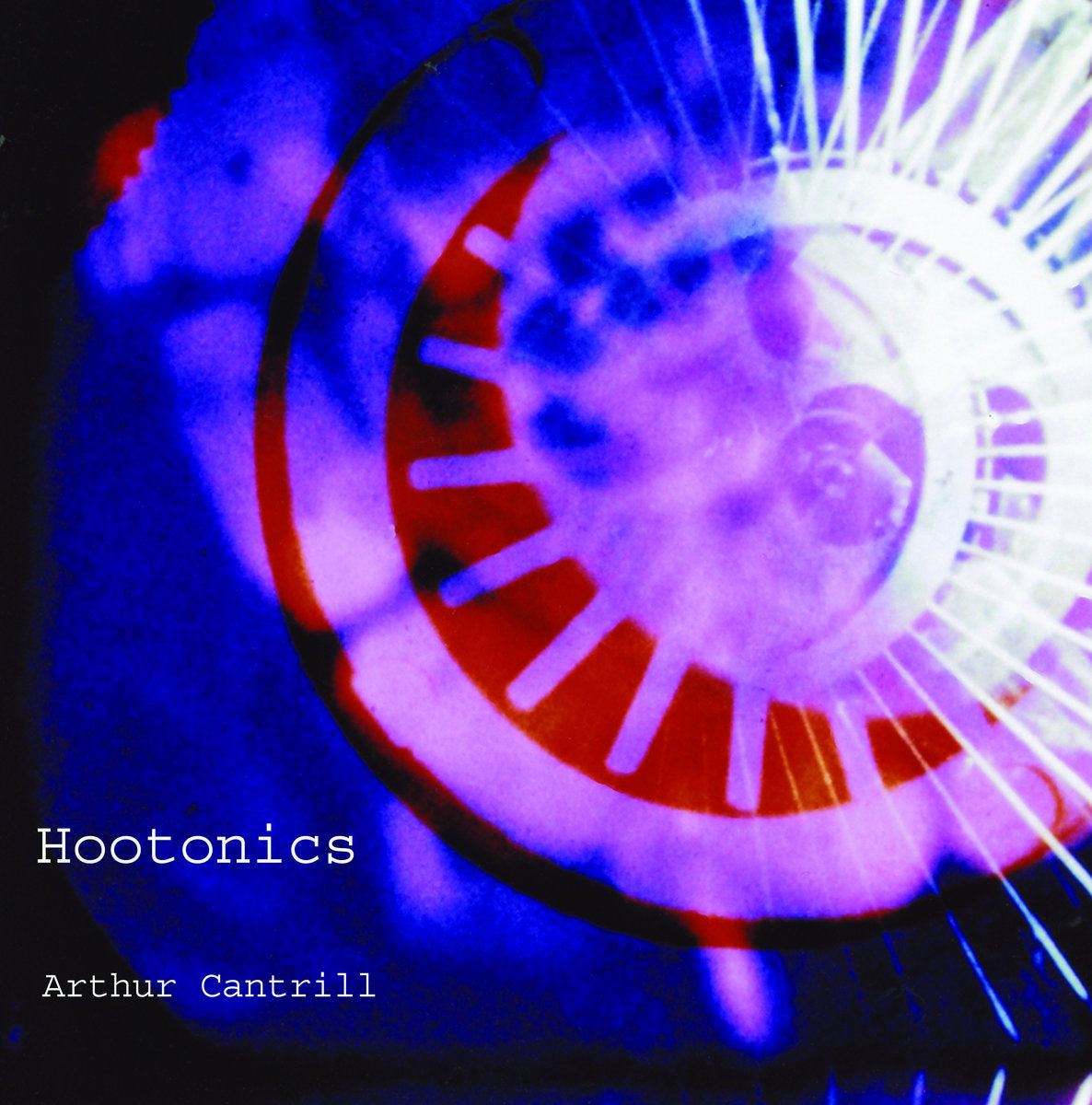

Arthur Cantrill - Hootonics LP

Arthur Cantrill - Hootonics LP

The titles of the tracks on this album refer to the sequences of the film they accompany.

My partner, Corinne Cantrill and I both knew Harry Hooton in Sydney in the 1950s before we met to start our 50-year filmmaking collaboration. In Sydney and Brisbane Corinne helped Hooton with advertising and sales of his magazine, '21st Century', while I met him through a mutual friend. Henry Arthur Hooton, known as 'Harry', born in England in 1908, arrived in Sydney in 1924, and by the 1930s and '40s he was being published in journals such as Meanjin Papers. Hooton developed his philosophy of Anarcho-technocracy (summed up as: man is perfect, so leave him alone and direct your creative/aggressive energies towards the materials of art and science). However by the 1950s he found it difficult to be published in Australia, although he had some recognition in the USA. This was an

impetus for launching his own literary magazine, '21st Century', in 1955. Hooton greatly impressed us all with his philosophy as expressed in his poetry and essays, and in his compelling mode of everyday conversation and discussion. Holding forth in pubs and cafes, he was a well-known figure in what became known as the

'Sydney Push'.

Fifteen years later, in 1969, during a Creative Arts Fellowship at the ANU, we were able to make the feature length experimental film Harry Hooton, which we had long wanted to do. It was not to be a biography, but a filmic interpretation of 'Hootonics' (as he called it), especially his definition of art as 'the communication of emotion to matter'. In our case the 'matter' was to be the material of film, sometimes

directly worked upon with coloured light and hand-printing.

Much of the film imagery reflects a prescient quote from Walt Whitman which begins the film: 'And I say to any man or woman, Let your soul stay cool and composed before a million universes' (from 'Song of Myself'). Whitman was one of HootonÕ' heroes - he read Whitman's 'Leaves of Grass' in his father's library in England - and Hooton and Whitman both had a similar declamatory style as well as a disregard for the rules of poetry. (Hooton: 'There are no rules for poetry / Necessity makes, and breaks all rules.')

The sound for our Hooton film had to support the image in conveying the visionary philosophy. In the preceding four years in London I produced film sound tracks using reel-to-reel tape editing and mixing, and musique concrete methods, and felt confident that something interesting could be done for the Hooton film. We added a Revox semi-professional reel-to-reel tape recorder to our Ferrograph and Nagra tape machines, and I was pleased to find that it had a reverberation facility that fed the signal from the replay head back into the recording head (the reverb interval increased when the machine changed from 7" to 3" per second). When taken to the extreme this resulted in a powerful pulsing white noise emerging from the reverb which could be controlled with precision. I set to work, feeding sea and other effects from the Nagra into the Revox and transforming the sound into something reminiscent of a 'million universes'. I had no access to a synthesizer, but the results were akin to synthesizer sound.

We had access to tapes Hooton recorded just before his death in 1961 in which he extemporized on his ideas and read his writing; roughly half of the sound for the 83 minute-film is Hooton's voice alternating with 40 minutes of sound compositions, which are never mixed with his voice. (His voice is not heard on this LP.)

One audio source for the compositions was the sound generated by computers at the CSIRO Division of Computing Research in Canberra, 1970. On our Nagra I recorded the extraordinary output from the early computing equipment: a high-pitched beeping and buzzing, which, when slowed down, became rather musical (the programmers told me this audio output provided information on the computer performance). When these were fed through the Revox reverb process a spacey dimension was added, the degree of which could be precisely controlled in real time, virtually an improvisation. These computer sounds are used throughout the film, sometimes emerging from the white noise pulsations, at other times carrying the sequence alone or as in 'Poem of Machines' used with shots of the CSIRO computer equipment, where the computer 'music' is heavily edited and intercut with mechanical sounds of the primitive computers in action: flipping punched cards, large hard drives etc...

Illustrating Hooton's concept of 'playtime on earth', human voices are also sometimes used in the mix, especially the voices of joyful students, with reverb added, used with repeated hand-printed shots of students at an ANU drama festival. Human voices are also used in 'ItÕs All Bunk' as a tightly edited and mixed collage of 1970 radio news voices, ending in reverb white noise.

The inch tapes were transferred to 16mm full-coat magnetic film, edited, and tracks were laid to the workprint for mixing down in a dubbing theatre by a sound mixer, who referred to a dubbing cue sheet I prepared.

The sound on this LP is a transfer from the 16mm magnetic mixdown to digital audio tape, made in 1996.

Bonus track 'Cicada Mix' - This is a recording of an improvisation I gave at Peter James' request in December 2011. Our track for 'Island Fuse' was on his 'Shape of Sound' Vol. 2 CD (Iceage Productions), and Peter suggested I could give a performance/demonstration of the analogue Revox feedback technique at the CD Launch, as there are elements of this in the 'Island Fuse' piece. I had recently made a mix of summer cicadas plus me responding to the cicadas on piano, violin and wooden xylophone (which was a 21st birthday present in 1959!) and fed this from the 50 year-old Nagra into the Revox running at 3_ inches per second to maximize the reverb effect. In real time I manipulated the volume controls to introduce varying degrees of the reverb/white noise, as I did 41 years earlier for the Harry Hooton tracks. It was automatically being recorded on the Revox during the impro, and that recording is used here.

- Arthur Cantrill, 2013